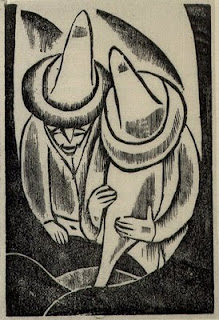

Lyonel Feininger (German/American 1871-1956), Volcano, 1918

This fall I am teaching relief printing as part of an introductory printmaking course. During the first class, I introduced examples of relief prints from art history. Many of these images are included in this post. After this presentation/lecture, students began to work on preparatory drawings that would lead them toward their own print. Although this stage of design can’t be seen in the prints shown here, during this sketch stage the treatment of one’s subject and its compositional layout can be considered and revised. Once a plan is made, the design is render on the surface of the carving block (usually linoleum or wood). When the drawing is in place then the remainder of the work revolves around carving and printing. Surprises can arise while carving, and adjustments can be made after a proof is printed. However, it is the initial planning which I believe to be the most critical to the success of this kind of print (one that relies on describing form).

The prints included in this post are related to German Expressionism and prints made in Mexico during the first half of the 20th century. When discussing these prints with the students, I asked them to notice how the negative space (the space around the main subject or subjects) can contribute to the organization of a picture. If the shapes that the negative spaces make are complex then this can lead to a more active image. Although a larger amount of white or black around a figure or subject can lead to a dramatic presentation, rarely is the background (or negative space) all white or all black in these examples. Here marks are often used to activate spaces that can be undervalued to the passive viewer. In other words, the type of mark made according to its width, length, and direction is integral and an important subject unto itself.

Francisco Dosamantes (Mexican 1911-1986), Scandal, 1945

Carving does not allow for shading but value differences can be created optically by the proximity of marks. The smaller and farther apart marks are the lighter a picture will appear. In other words, the more one carves the lighter the image will be when printed because there will be less raised surface area for the ink roller to make contact with. However, exceptions will occur when the printing method involves explicitly over inking the matrix or that the carved marks remain too shallow and collect ink.

Below are examples with notes and links. Some of the artists are less known and I am pleased to include them here because they made important contributions to the larger milieu of their time and culture.

Karl Jakob Hirsch (German 1892-1952), Self Portrait, 1915

Franz M. Jansen (German 1885-1958), 8 O’clock, 1920

Käthe Kollwitz (German 1867-1945), The Widow II, 1923

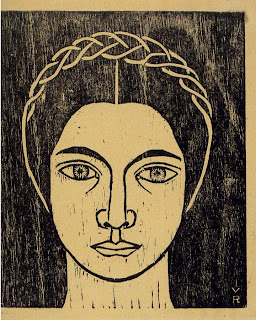

Isabel Villaseñor (Mexican 1909-1953) Self Portrait, 1929

I could not find a lot of information about Villaseñor. She was a poet and artist who also appears as a model in many well regarded photographs.

Tamiji Kitagawa (Japanese, 1894-1989) Extracting Sap from a Maguey Plant, 1930

Tamiji Kitagawa was born in Japan but came to live in Mexico.